| Wisdom and Knowledge - Leadership in Balance |

|

"Knowledge is of the past, wisdom is of the future" (Vernon Cooper) "To know that you know what you know, and that you do not know what you do not know, that is true wisdom." (Confucius) "Never mistake knowledge for wisdom. One helps you make a living; the other helps you make a life." (Sandra Carey) At that time the kingdom of heaven will

be like ten virgins who took their lamps and went out to meet the

bridegroom. Five of them were foolish and five were wise. The foolish

ones took their lamps but did not take any oil with them. The wise,

however, took oil in jars along with their lamps. The bridegroom

was a long time in coming, and they all became drowsy and fell asleep.

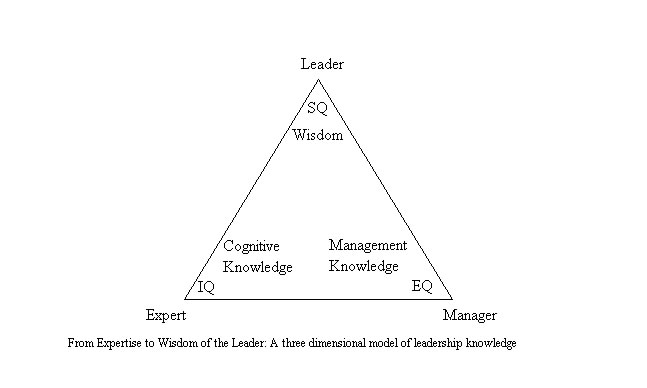

We perceive ourselves to live in a knowledge society which requires us to acquire knowledge in order to be able to solve the problems ahead of us. We learn how and when to use which tools and how to apply them to given problems. However, we still seem to fail at an astonishing rate, given the increasing amount of knowledge that has been collected. Complexity of life appears to go beyond the problem-solving knowledge we tend to apply. Uncertainty of our future calls for wisely accepting our ignorance without loosing confidence in what we do know and to act accordingly. This article suggests reconsidering a development of wisdom by balancing our knowledge and ignorance based on a three-dimensional approach to knowledge and human intelligence. Approaches to knowledge - Concepts of Intelligence Introduced by Binet (1916), the concept of "intelligence" and testing a set of cognitive skills and abilities started decades of psychological research and the development of numerous testing tools (Fancher 1985). Based on his studies of performance in leadership, Daniel Goleman (1995) presented his concept of "emotional intelligence" and the importance of feelings for high performance in the work environment. Finally, Zohar & Marshall (2001) argued that there is a third and "ultimate intelligence", which we use to discover values and find meaning, the main motif of human action (Frankl 1984). "Cognitive" Intelligence - Knowledge of the expert Quantifying intellectual capabilities stood at the beginning of research on and application of intelligence testing. Diagnosis of the "intelligence quotient (IQ)" (Binet 1916; Fancher 1985; Eysenck & Eysenck 1985) measures the ability to solve logical or strategic problems. The results of the respective diagnostic tools are still used for prognosis of cognitive capabilities and performance in various settings. The higher the test scores, the higher the "intelligence" of the tested person, is the basic concept of this approach. In fact, studies have shown the significant relationship between cognitive intelligence and job performance (Hunter 1986). However, discussions about what set of capabilities should be included and with what weight still go on and a variety of diagnostic tools exist. Sternberg (1985) has made the point in particular, that "analytic" intelligence needs to be enhanced by "practical intelligence" (capability to solve problems) and "creative intelligence" (capability to find new approaches). Most modern concepts of cognitive intelligence seem to include the three categories of "crystallized intelligence" (ability to apply acquired knowledge to current problems), "visual-spatial reasoning" (ability to apply visual representations to problem solving) and "fluid intelligence" (ability to develop problem solving techniques for problems unknown to the problem solver) (Cattell 1971; Horn 1985; Hunt 1995). All three categories seem crucial for solving the problems of our environment: While crystallized intelligence helps us apply our bodies of knowledge to problems at hand, visual-spatial reasoning supports system-thinking and many other tools and techniques used in our professions and fluid intelligence lets us cope with the non-standard problems we may encounter. However, the focus still remains on intellectual capabilities and cognitive knowledge. The major anthropological assumption appears to be the perspective on human beings as being rational information processing and problem-solving species. However, philosophers and psychologists have continuously rejected the notion of intellectual capabilities being the only or most important characteristic differentiating human existence from other species. "Emotional" Intelligence - Management knowledge Probably the most influential approach introducing an additional dimension into differentiating between high and low performance in management and leadership was Goleman's (1995) concept of emotional intelligence (EI). In integrating similar approaches of other neurologists and psychologists (Rosengren et al. 1993; Gardner 1993; Lewis et al. 2000) Goleman has discovered the ability to access one's own and others' personal feelings as crucial for both, the cognitive intelligence to become effective and for achieving high performance in professional settings and work environments. In his research, Goleman (1995, 1998, 2004) has collected and analyzed data from almost 500 global companies in order to identify the factors most influential on the organizations' performance. Besides technical skills and cognitive capabilities he studied emotional intelligence factors such as self-awareness and relationship skills. His findings confirmed earlier research indicating that in an environment of rather high IQ, technical skills and cognitive capabilities were of rather low differentiating importance compared to emotional intelligence factors. Hence, while the IQ seems necessary for professionals to do their job decently, EI competencies and the respective knowledge seem to make them excel. The sets of competencies that Goleman (2004) identified to account for high performance are as follows (ibid. pp. 253-256): Self-Awareness: emotional self-awareness, accurate

self-assessment and self-confidence. Undoubtedly the capabilities to appropriately cope with the challenges of one's own personality as well as the skills to create and sustain buy-in and cooperation are of major importance in any organizational environment. Expertise may help to get professional assignments done. But when it comes to balancing the often conflicting and changing requirements, leaders additionally need EI competencies to meet the expectations of various stakeholders. By incorporating emotions and the management of relationships, this approach goes beyond the approach of cognitive intelligence and expertise. It fails, however, to explicitly refer to the human ability and need to strive for values and a meaningful life in spite of or in the midst of increasing uncertainty and complexity. While contributing to the confidence in ourselves and others, it does not address the challenges that arise from the discovery of our limitations and ignorance. "Spiritual" Intelligence - Wisdom of the leader While values and meaning have increasingly come to the forefront of management theory and education (Paine 2003; Covey 1989), the concept of Spiritual Intelligence (SQ) introduced by Zohar & Marshall (2001) and based on respective neurological, psychological and anthropological research (Frankl 1984; Singer & Gray 1995; Chalmers 1996, 2004; Llinas 1998) is the first comprehensive model of human intelligence incorporating the human search for values and meaning. By SQ Zohar & Marshall (2001) refer to "the intelligence with which we address and solve problems of meaning and value, the intelligence with which we can place our actions and our lives in a wider, richer, meaning-giving context, the intelligence with which we can assess that one course of action or one life-path is more meaningful than another" (ibid. p. 3f). Integrating all our intelligences and making us the truly human being, SQ is the "ultimate intelligence" (ibid. p. 4). Based on Frankl's (1984) research indicating that "man's search for meaning is the primary motivation in his life" (p. 121) Zohar & Marshall (2001) hold that SQ is the major capability of asking "why?" and of answering that question by being able to find meaning in everything we do and experience. Thus, we are also able to question the rules and situations we are confronted with. Therefore, SQ goes beyond the abilities to intelligently think, feel, act and behave within a situational context or a given framework. SQ allows human beings to wisely reflect on the very situation and frame of reference they find themselves in and creatively and meaningfully transform it into something new and more valuable if they so choose. The concept of SQ directly relates to the understanding of wisdom as an attitude to question truth, exhaustiveness and validity of beliefs, values, knowledge, information, skills and abilities through "curiosity, openness, and complex sensing" (Weick, 2001, p. 113). Wisdom as a "deeper understanding of reality" (Robinson, 1990, p. 22) needs to go beyond a "technical knowledge" of how things work or of how people interact. Our attempt to answer the questions of "why" and "what for" through wisely applying spiritual intelligence calls for openness to and discovery of yet another dimension. Wisdom and spiritual intelligence accept the limitations and fallibility of our knowledge and avoid being too confident in our knowledge without becoming overly cautious and concerned with our ignorance. They help us keep a "balance between knowing and doubting" (Meacham, 1990, p. 210). These spiritual capabilities are crucial when it comes to intelligently and comprehensively identify organizational requirements, to meaningfully communicate with stakeholders and create buy-in based on a joint vision and shared values, and to transform organizations into something new and more meaningful by wisely coping with the challenges of change, crisis and loss that we inevitably face in most of our increasingly complex environments (Mengel et al. 2004). Beyond control: the limitations of professional knowledge and management know-how Our bodies of general and management knowledge are presented by "breaking it down" into various areas. Thus, traditional models of management knowledge analyze the basic know-how ("cognitive intelligence") necessary to become professionals (e.g. for the area of project management see: Jafari 2003; Project Management Institute 2000, 2004; Zwerman et al. 2004). This level of knowledge is associated with high levels of analytic skill and a focus on control. Enhancements put this knowledge into a situational perspective. Hence, they provide initial insights into the know-where, -when, and -who ("emotional intelligence") to manage the knowledge application in a way responsive to its environment (Goleman 1995, 2004). This knowledge may be sufficient to provide experts and managers with the knowledge and management tools necessary to master the challenges within an environment of low or moderate complexity and uncertainty. However, it appears to be insufficient to enable them to wisely lead the changes inherent in complex adaptive organizations (Aram and Noble, 1999; Jafari, 2003 ; Ruuska and Vartainen, 2003). Research suggests that "leadership and socio-cultural competencies become critical …[while] the current models for professional preparation and certification tied to the normative approach are ill-suited to the emerging complex society" (Jafaari 2003, p. 56; Lester 1994; Robinson 2000). Stacey (1993) even suggests that the simplified model of reality as input-process-output may be a distortion that should not be applied at all to organizations where events and encounters may anytime change the future in a unpredictable way. Thus we have to acknowledge the need for a much more creative and reflective approach in addition to the normative base as suggested by our bodies of knowledge. Leaders must understand why things work to be able to adapt practises to situations. This capacity to discover and contemplate the know-why ("spiritual intelligence" and wisdom) will empower the leader to synthetically "break up" frameworks and references that are no longer of value. Thus, spiritually intelligent managers will be able to lead the way to creating and implementing new visions by transcending traditional frameworks and by finding new meaning for activities, projects and programs on any level (Zohar & Marshall 2001; Jafari, 2003; Mengel et al. 2004). The knowledge requirements of this values-oriented leadership approach (Mengel 2003, 2004) are explored in the next section. The wisdom of values-oriented leadership: the knowledge of creativity and discovery To reach the leadership level we need to recognize and better understand our biases that are related to our focus on problem solving rather than on "seeking first to understand" (King 1999). At first, the rush to solve the problem in front of us by immediately applying the models at hand and without questioning their assumptions and implications may hinder discovering the model to be part of the problem. Our linear logic restricts awareness and understanding of context and relations. Thus creativity and holistic thinking should be the focus of our education. Furthermore, people tend to feel safer in a familiar and well-organized environment where they appear to be at home and in control. Especially in stressful situations typical for most professional environments we tend to avoid further exposure to insecurity and focus on solving problems within the frameworks we feel comfortable with rather than trying first to understand. Finally, we need to unlearn the "ideal of scientific detachment" (ibid. p. 125), the logical myth of reason and emotion being separate. Only if people succeed to emotionally identify with common objectives are they willing to understand individual behaviour, goals and motifs and share values. In order to "discover" new meaning and values (Frankl 1981), King (1999) suggests that we first need to uncover and overcome our biases by learning to withdraw temporarily from comfortable environments like prophets. This will enable us to get to "know ourselves" and to discover new values and meaningful perspectives. It will help us to wisely accept our limitations and ignorance without totally loosing confidence in what we do know (Weick, 2001). Only then will we be able to understand how to transform reality accordingly and still being prepared for the unexptected. Moving from analysis to synthesis, from breaking down to integrating, from knowing to understanding, from asking "how to" to "when, where, why?" (King 1999, p. 116; Lester 1994) and integrating emotional and spiritual intelligence as well as the wisdom of balance into our cognitive approaches will move us ahead. It will help us grow from novice to competent and proficient performers and finally to become experts (Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1986) that are emotionally and spiritually intelligent and wisely accept their limitations. As leaders we will be capable of leading, creating and transforming our environment rather than reacting to the inevitable changes and challenges facing us. Cognitive approaches will help us identify what is, emotional approaches may provide us with insight as to how people feel about what is and thus help us to intuitively understand the dynamics of where we are going. Finally, the spiritual capabilities may help us grasp new meaningful options of where to go and what to be prepared for. Personal development towards knowing ourselves (the ability to understand why we do what we do and the way we do it) is a major step towards understanding others (the ability to understand why others do what they do and the way they do it) and towards learning how to influence both towards solving crucial problems ahead of us and accepting what we cannot change; it may also help us develop the wisdom to differentiate between the two. This comprehensive knowledge will enable us to intelligently apply our bodies of knowledge successfully. Meaningful communication based on listening and striving for mutual understanding will help us develop wisdom by acting as if we were right, but remaining attentive as if we were wrong (Weick, 2001). Conclusion The problems we face in a world of complexity and uncertainty are "wicked" rather than "rational/analytic". Today's leaders need to be more than proficient in their ability to flexibly and creatively adapt to and transform the rapidly changing complex systems they work in. The nature of the intelligence and knowledge base to work in this world is far broader than simply analytic. While cognitive intelligence and expert knowledge enables us to manage projects within a controllable environment of limited complexity and low uncertainty, emotional intelligence and management knowledge are required when dealing with increasingly complex project environments. In order to be able to provide leadership in highly complex and uncertain project environments leaders additionally need spiritual intelligence, the leadership skills and wisdom to help discover meaning and to help create new and valuable environments through jointly making sense of what we do and do not understand. They need to share responsibility and leadership when creating the future while keeping watch and being prepared for the unexpected.

|