How does one succeed in life? Of the infinite number of answers to this enduring question proposed by philosophers and educators alike, existential positive psychology (EPP) provides one of the strongest based on the synthesis of ancient wisdom and modern research. Wong (2005a) concisely outlines the EPP solution:

“You need a high IQ [intelligence quotient] to excel in school. You need a superior EQ [emotional quotient or emotional intelligence] to do well in business. You need to constantly improve your LQ [life quotient or life intelligence] to succeed in life.”

The rationale? Wong and colleagues (in press) explain that:

“Without LQ, we can easily walk into a mine field or fall into some kind of trap. Even successful people with high IQ and EQ can ruin their careers because of sexual discretion, hubris, greed, abuse of power, and foolish decisions and unethical behaviors, because they have the illusion that they can get away without paying the consequences.”

How does one become life intelligent? There is the easy way and the hard way. The hard way involves making mistakes, both small and large, and learning from those tough lessons. One example could be wasting one’s life on meaningless things and realizing later that one was not living authentically or meaningfully. Conversely, the easy way entails studying or listening to the wisdom of others (e.g., philosophers and sages, one’s ancestors, friends, and family) and learning about the realities of life. If one has read Man’s Search for Meaning (Frankl, 1946/1985) for instance, then they may be more aware of their responsibility to discover the meaning of their life and to make the most out of the remaining time that they have.

In these two examples of learning about life, the harder way involves much suffering; however, the easier way involves something called life education. Although life education may sting because the realities of life are bitter and sometimes hard to accept, it is clear that this short-term pain may save individuals from unnecessary suffering down the road.

Given the important contributions of life intelligence and, therefore, life education to wellbeing, this article seeks to answer two questions: Firstly, what exactly is life intelligence? And secondly, how can one be more life intelligent through life education? I will answer these questions by focusing on EPP principles, while bringing in research on Gardner’s existential intelligence and the recent psychological construct of wisdom.

Existential Intelligence and Life Intelligence

Within EPP, life intelligence (LQ) is similar to Gardner’s (1999, 1983/2011) concept of existential intelligence (Wong et al., in press). In Gardner’s influential theory of multiple intelligences, existential Intelligence is all about one’s capacity to understand and think about the big questions regarding one’s existence, such as the meaning of life (Gardner & McConaghy, 2000; Johnson, 2022). In their discussion about existential and spiritual intelligences, Halama and Stríženec (2022) view existential intelligence as primarily one’s ability to find and realize adequate life meaning. McKenzie (1999) created a brief survey to measure all of Gardner’s (1983/2011) nine types of intelligences, including existential intelligence. Some items pertaining to existential intelligence includes “It is important to see my role in the ‘big picture’ of things,” “I enjoy discussing questions about life,” and “It is important for me to feel connected to people, ideas and beliefs.” One line of research, led by Hajhashemi and colleagues, has validated and utilized McKenzie’s survey in different countries, such as Iran (Hajhashemi & Wong, 2010) and Australia (Hajhashemi et al., 2018).

Wong has written extensively on the need for LQ for a deep life of resilience and meaning. Earlier on, Wong (2005a) defined LQ simply as “intelligence for life, intelligence for living.” In the same article, he also laid out the reasons why LQ is needed (e.g., high IQ and EQ are insufficient for many of life’s challenges), explored the aspects of LQ (e.g., having a clear sense of one’s mission and responsibility), compared high and low LQ individuals (e.g., the difference between using one’s time wisely and foolishly), and described what triggers one’s quest for LQ (e.g., realizing that one’s like is spinning out of control). Like Halama and Stríženec (2022), Wong also views LQ as analogous to discovering meaning in life.

Although Wong has compiled a rather extensive list over the years of what it means to be “life intelligent,” in recent lectures, more recently he has refined the list to a set of core principles or aspects of LQ (Wong, 2017, 2022a, 2022b, 2022c). Life intelligent individuals:

- Have accepted life with gratitude (both the positive and negative sides of life).

- Have discovered the meaning of life, death, and suffering.

- Believe that they can create a better future (with God’s help).

- Are committed to a worthy life purpose.

- Are enjoying life and making the best use of one’s time.

- Are courageous in transcending limitations and obstacles.

- Are constantly digging deeper by transforming the dark side of life.

Additionally, life intelligent individuals understand:

- How to live and die well.

- How to cope with changes and uncertainty with wisdom and grit.

- How to become one’s best self.

- How to relate with others in an interconnected global society.

- That suffering is necessary for flourishing and mature happiness.

- That one is responsible for one’s own wellbeing, as well as the wellbeing of others.

- That one needs to love and serve other people as well as have a higher power to avoid inflicting unnecessary suffering on oneself and others (boundaries).

LQ requires awakening, faith, and passion: one needs to be awakened to the realities of life, to take a leap of faith in pursuing what is good (whether that is truth, virtue, justice, or a better future), and be committed to one’s mission with passion, even if one’s mission is impossible to accomplish. Essentially, these three elements are necessary stepping-stones to experience deep joy, as illustrated in the following diagram from Wong (2022b).

The following diagram (Wong, 2022c) captures the core principles of Wong’s understanding of LQ.

Life Intelligence and Wisdom

LQ is all about wisdom. Ideas about wisdom have historically been reserved for philosophers (e.g., Plato, Aristotle) and religious traditions (e.g., Book of Ecclesiastes, the Qur’an). A half century ago, psychologists began to examine the basis and development of wisdom through a scientific lens (Bluck & Glück, 2005; Grossmann et al., 2020; Oser et al., 1998; Nusbaum, 2019; Staudinger & Glück, 2011). The modern psychological construct of wisdom contains many of the features that are core to Wong’s construct of LQ, such as the Aristotelean concept of phronesis (or practical wisdom).

I will now briefly compare the two constructs to illustrate other similarities. In Staudinger and Kessler’s (2009) integrated model of wisdom, the cognitive component captures the deep and broad insights that wise people have about life and death. These insights are often paradoxical and unexpected. Grossmann and colleagues’ (2020) common wisdom model also features a cognitive component. In their view, wise people often view issues from a meta-cognitive perspective, allowing them to utilize different perspectives to attain deeper insight (to dig deeper) into those issues (also known as perspectival aspects of meta-cognition). Wise people tend to have discovered some meaning of life, death, and suffering, and understand how to live and die well. If one understands that the meaning of life is that it should be lived (like Bruce Lee), then they would commit themselves to some worthy life goals and would make the best use of one’s time. Wise people would understand that suffering is necessary for flourishing and happiness, how to transform and transcend the dark side of life, and how to become one’s best self despite obstacles and limitations.

Additionally, using a meta-cognitive perspective, wise individuals tend to understand how to navigate the basic dialectics of human existence, such as positivity/negativity and selfishness/altruism (Staudinger & Glück, 2011). They embrace the contradictions in life and strive towards balance and equilibrium. They are more likely to be aware of the necessary relationship between the positive and negative sides of life and are therefore more likely to accept both with gratitude. Understanding the dialectics of life also allows wise people to relate with others in an interconnected global society where people have different background and interests.

Moreover, the motivational component of the integrated wisdom model details how wise people tend to act in a self-transcendent, altruistic way by being invested in the wellbeing of the global community and improving the human condition (Oser et al., 1999). The common wisdom model (Grossmann et al., 2020) also emphasizes moral aspirations as a necessary criterion of wisdom. This includes the pursuit of truth, orientation towards the common good, and balance of self-protective and other-oriented interests. Wise individuals are more likely to believe that they can create a better future, understand that one is responsible for the wellbeing of oneself and others, and that one needs to love and serve other people as well as a higher power to avoid inflicting unnecessary suffering on oneself and others (horizonal and vertical self-transcendence; Wong et al., 2021).

Finally, the emotional component of the integrated wisdom model includes complex emotion regulation and tolerance of ambiguity. Thus, wise people are more likely to cope with changes and uncertainty with grit and equanimity.

In short, the psychological constructs of LQ and wisdom have much in common even if the first is more existential while the latter is more cognitive in nature. Given the importance of LQ and wisdom in helping us navigate the challenges of life, one might wonder: is there any way to be more life intelligent or become wiser?

Life Education

In the existing literature, the concept of life education involves teaching individuals to respect and cherish life (Ding, 2008); teaching life wisdom, life practice, and life care (Phan et al., 2020); and providing moral education to help individuals understand the real meaning of life (Chen et al., 2021; Yu & Jing, 2013). Interestingly, some educators believe that life education should be a fundamental part of physical education (“people-oriented physical education”; Ding, 2008; Yu & Jing, 2013). Their rationale is that good education requires educating the entire person, including the existential-spiritual dimension.

Within the framework of EPP, Wong (2017) has a similar rationale regarding the need for life education. True success in life depends on whether one becomes a fully functioning human being by developing their mind, heart, body, and community life (i.e., the development of the entire person). Only life education can guide individuals to develop these inner potentials so that they can live a meaningful life while contributing to their community. Additionally, given the many dangers in life, whether they are external (e.g., the pandemic, war, peer-pressure, relational conflict) or internal (e.g., ego, carnal desires, unresolved conflicts), life education can help protect individuals from avoidable trouble and suffering (Wong, 2005a).

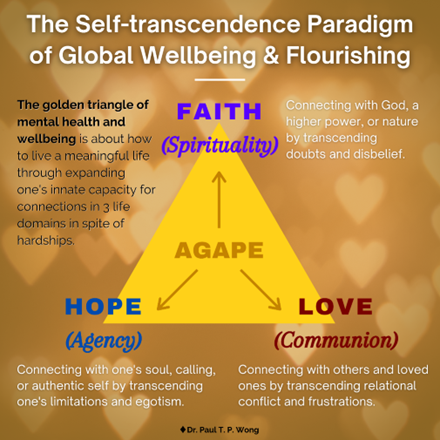

What does life education look like from a EPP perspective? It involves teaching people life intelligence, connectedness, compassion, and courage. Life intelligence, as I have detailed above, helps us navigate the storms in life. Regarding connectedness, good mental health requires us to be connected with our true self (authenticity, hope), with others (love), and with a Higher Power (faith). These components represent the three corners of Wong’s (2020) model of mental health: The Golden Triangle.

Related to connectedness is compassion. Whether one follows the golden rule or Kant’s categorical imperative, we need to be compassionate towards others to withstand the struggles of life. After all, we are all in the same boat travelling through the storms in life. Additionally, if we are compassionate, we have a higher chance of being connected not only to others, but to oneself (self-compassion; Neff, 2011).

Additionally, we need the courage to accept, transform, and transcend unavoidable suffering and limitations. For instance, we need the courage to choose the future rather than the past in our decision making, even if we experience ontological anxiety from choosing the unknown (Maddi, 2004; Tillich, 1963). The alternative – the accumulation of ontological guilt (regret over an unlived or poorly lived life) – is worse. This is the basis of Wong’s (2020) model of resilience: The Iron Triangle. For more information on how to develop connectedness, compassion, and courage, the essential elements of life intelligence, see Wong (2005a, 2005b, 2005c, 2005d, 2017).

Given the important functions of life education, what about the elements? The following diagram from Wong (2017) illustrates the elements of his life education model. As the foundation of life education, the entire community needs to support the individual in his or her life education. Building on this foundation, the five cornerstones of faith, hope, love, knowledge, and courage represent the five cornerstones that one needs to deal with adversity in life. The four walls and five tools are derived from Wong’s (2012) dual-systems model for what makes life worth living. PURE and ABCDE are also core features of Meaning Therapy (Wong, 2010) and both are essential for flourishing. The result of life education and gaining life intelligence is mature happiness (Wong & Bowers, 2018), which, unlike hedonic and eudaimonic happiness, is more durable under stress and suffering.

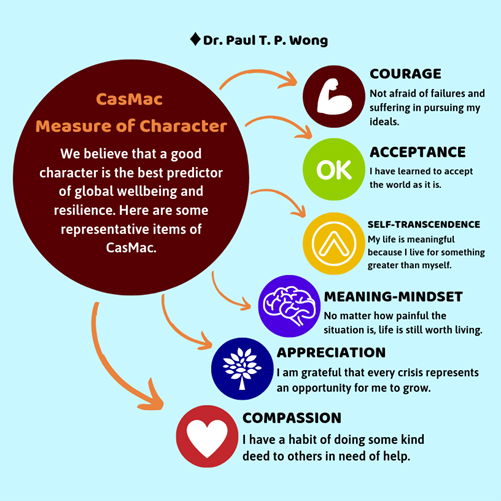

Chen and colleagues (2021) recently explored the effectiveness of life education (or “meaning-centered positive education”) in a university setting. Inspired by Wong’s (2020) CasMac model of EPP (see the following diagram), they developed a 15-week curriculum for 38 Taiwanese university students that aimed to teach students courage, acceptance, self-transcendence, meaning, appreciation, and compassion. The teachers encouraged the students not only to write reflections, but to also practice PP2.0 outside of the classroom (e.g., doing volunteer work, trying something new, applying the ABCDE model in everyday settings). At the end of the 15 weeks, the researchers compared the treatment and control group through a self-report questionnaire and found that the treatment group showed higher levels of courage, self-transcendence, meaning, and appreciation than the control group. Although the sample size was quite small, there was no control group, and students were measured only using self-report measures, this study provides preliminary evidence that a brief intervention in an educational setting can help university students become more life intelligent. More research is needed to confirm these findings.

Wisdom Training and Teaching

According to the wisdom literature, like LQ, wisdom can develop naturally throughout the lifespan without training or interventions. However, being older does not guarantee that one is wiser (Grossmann et al., 2020). Instead of age, researcher have found that specific life experiences and activities can help people become wiser, including participating in certain meditation practices (e.g., loving-kindness meditation, mindfulness meditation decentering, self-distancing), activities that encourage perspective taking, and exploratory processing after difficult life experiences (Grossmann et al., 2020; Nusbaum, 2019; Westrate & Glück, 2017).

Given the above correlates of wisdom, several groups of researchers have examined whether it is possible to increase wisdom through wisdom training. After all, Plato (2012) as well as Aristotle emphasized the important of cultivating practical wisdom (phronesis) through education (Kristjánsson, 2021). As stated earlier, much of modern wisdom research is focused on practical wisdom. Earlier research provides some evidence of the effectiveness of wisdom training. Staudinger and colleagues (2006) found that structured self-reflection training was associated with immediate increases in personal wisdom. In a therapeutic setting, mindfulness training and deliberate practice (i.e., thinking critically or dialogical thinking) may also increase wisdom (Hanna & Ottens, 1995; Lieberei & Linden, 2011).

In an education setting, there have been attempts to incorporate wisdom training and teaching for many age groups across different cultures (Ferrari & Potworowski, 2008; Sternberg et al., 2009). Some examples include reading classical wisdom literature, practicing dialectical thinking, training in mindfulness, pairing students with a “wisdom mentor,” and encouraging students to reflect on their own values and beliefs (Staudinger & Glück, 2011).

Most wisdom training and teaching curricula are not empirically supported but there are a few exceptions (Ardelt, 2020; Bruya & Ardelt, 2018; DeMichelis et al., 2015; Sharma & Dewangan, 2017). For instance, Bruya and Ardelt (2018) reported that self-reflection journaling, rather than self-cultivating journaling on character strengths, can help university students develop some aspects of wisdom. Building on these findings, Ardelt (2020) recently examined whether holistic teaching (teaching that addresses the whole person rather than just the intellect) could increase wisdom, too. Of a total sample size of 321 students, half were assigned to take courses that had a service-learning component (treatment group), including a mindfulness practice, a spiritual life review, volunteering, and self-reflective journaling, while the other half (control group) took similar courses without a service-learning component. Interestingly, the service-learning course component utilized by Ardelt is quite similar to the life education curriculum developed by Chen and colleagues (2021). At the end of her study, Ardelt (2020) found that the students that took the service-learning courses had higher levels of wisdom on every dimension (cognitive, reflective, and compassionate), as well as higher levels of psychological wellbeing, spirituality, and death acceptance. Ardelt’s study provides good evidence that incorporating wisdom training/teaching in a university curriculum can help students with their psychosocial growth.

Conclusion

Although the positive effects of life education and wisdom training are promising, there is still much work to be done. As discussed above, there has only been a handful of studies looking into the benefits of including these forms of education in the school curricula. One interesting question is whether life education not only promotes student wellbeing but also prevents students from experiencing unnecessary suffering, such as harming oneself or others. I live in North America (Toronto) where cases of school violence, such as bullying, stabbings, and shootings, are becoming more common (AFP News, 2022; Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 2016). Additionally, the suicide rates among North American students are skyrocketing. One study found that suicide is the second leading cause of death among people aged 15 to 24 in (Cohen, 2022). I leave you with the following questions: Would life education help prevent such tragedies? Should there be more funding devoted to life education and wisdom training/teaching in schools?

References

Ardelt, M. (2018). Can wisdom and psychosocial growth be learned in university courses? Journal of Moral Education, 49, 30-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2018.1471392

AFP News. (2022, May 24). Two decades of deadly gun violence in US schools. International Business Times. https://www.ibtimes.com/two-decades-deadly-gun-violence-us-schools-3519765

Bluck, S., Gluck, J. (2005). From the inside out: people’s implicit theories of wisdom. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Jordan (Eds.), A handbook of wisdom: Psychological perspectives (pp. 84–109). Cambridge University Press.

Bruya, B., & Ardelt, M. (2018). Wisdom can be taught: A proof-of-concept study for fostering wisdom in the classroom. Learning and Instruction, 58, 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.05.001

Chen C.-H., Chang, S.-M., & Wu, H.-M. (2021). Discovering and approaching mature happiness: The implementation of the CasMac Model in a university English class. Frontiers in Education, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.648311

Cohen, S. (2022, March 15). Suicide rate highest among teens and young adults. UCLA Health. https://connect.uclahealth.org/2022/03/15/suicide-rate-highest-among-teens-and-young-adults/

DeMichelis, C., Ferrari, M., Rozin, T., & Stern, B. (2015). Teaching for wisdom in an intergenerational high school English class. Educational Gerontology, 41(8), 551–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 03601277.2014.994355

Ding, Z. (2008). Exploring life education in physical education curriculum. Chinese Journal of Physical Education, 15(6), 70-74.

Ferrari, M., & Kim, J. (2019). Educating for wisdom. In R. J. Sternberg, & J. Glück (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of wisdom (pp. 347-371). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108568272.017

Ferrari, M., & Potworowski, G. (Eds.) (2008). Teaching for wisdom: Cross-cultural perspectives on fostering wisdom. Springer

Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. Washington Square Press. (Originally published in 1946)

Gardner, H. (1999). Are there additional intelligences? The case of naturalist, spiritual and existential intelligences. In J. Kane (Ed.), Education, information and transformation (pp. 111-131). Prentice Hall.

Gardner, H. (2011). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Hachette UK. (Originally published in 1983)

Gardner, H., & McConaghy, T. (2000). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. ATA Magazine, 80(3), 6.

Grossmann, I., Weststrate, N.M., Ardelt, M., Brienza, J.P., Dong, M., Ferrari, M., Fournier, M.A., Hu, C.S., Nusbaum, H.C., & Vervaeke, J. (2020). The science of wisdom in a polarized world: Knowns and unknowns. Psychological Inquiry, 31, 103-133. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2020.1750917

Hajhashemi, K., & Wong, B. E. (2010). A validation study of the Persian version of Mckenzie’s (1999) multiple intelligences inventory to measure MI profiles of pre-university students. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities (JSSH), 18(2), 343-355. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-288829

Hajhashemi, K., Caltabiano, N., Anderson, N., & Tabibzadeh, S. A. (2018). Multiple intelligences, motivations and learning experience regarding video-assisted subjects in a rural university. International Journal of Instruction, 11(1), 167-182.

Halama, P., & Stríženec, M. (2004). Spiritual, existential or both? Theoretical considerations on the nature of “higher” intelligences. Studia Psychologica, 46(3), 239-253.

Hanna, F. J., & Ottens, A. J. (1995). The role of wisdom in psychotherapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 5(3), 195–219. https://doi.org/10. 1037/h0101273

Johnson, S. (2022, May 10). What is existential intelligence? Language Humanities.org https://www.languagehumanities.org/what-is-existential-intelligence.htm

Kristjánsson, K. (2021). Twenty-two testable hypotheses about phronesis: Outlining an educational research programme. Br. Educ. Res. J., 47, 1303-1322. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3727

Lieberei, B., & Linden, M. (2011). Wisdom psychotherapy. In M. Linden & A. Maercker (Eds.), Embitterment: Societal, psychological, and clinical perspectives (pp. 208–219). Springer Vienna. https:/doi.org/10.1007/ 978-3-211-99741-3_17

Maddi, S. R. (2004). Hardiness: An operationalization of existential courage. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 44(3), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167804266101

McKenzie, W. (1999). Multiple Intelligences Survey. Surfaquarium. https://surfaquarium.com/MI/inventory.htm

Neff, K. (2011). Self-compassion: Stop beating yourself up and leave insecurity behind. HarperCollins Publishers.

Nusbaum, H. C. (2019). Wisdom develops from experiences that transcend the self. In J. A. Frey & C. Vogler (Eds.), Self-transcendence and virtue: Perspectives from philosophy, psychology, and theology (pp. 225-250). Routledge.

Oser, F. K., Schenker, C., & Spychiger, M. (1999). Wisdom: An action-oriented approach. In K. H. Reich, F. K. Oser, & W. G. Scarlett (Eds.), Psychological Studies on Spiritual and Religious Development (pp. 85–109). Pabst.

Phan, H. P., Ngu, B. H., Chen, S. C., Wu, L., Lin, W., & Hsu, C. (2020). Introducing the study of life and death education to support the importance of positive psychology: An integrated model of philosophical beliefs, religious faith, and spirituality. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 580186. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.580186

Plato. (2012). The republic. The Big Nest. http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.5.iv.html

Royal Canadian Mounted Police. (2016, June 21). School violence. https://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/cycp-cpcj/violence/sv-ve/index-eng.htm

Sharma, A., & Dewangan, R. L. (2017). Can wisdom be fostered: Time to test the model of wisdom. Cogent Psychology, 4(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2017.1381456

Staudinger, U. M., & Glück, J. (2011). Psychological wisdom research: Commonalities and differences in a growing field. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 215–241. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131659

Staudinger, U. M., & Kessler, E. -M. (2009). Adjustment and growth—two trajectories of positive personality development across adulthood. In M. C. Smith & N. DeFrates-Densch (Eds.), Handbook of research on adult learning and development (pp. 241–268). Routledge.

Staudinger, U. M., Kessler, E.-M., & Doerner, J. (2006). Wisdom in social context. In K. W. Schaie & L. Carstensen (Eds.), Social structures, aging, and self-regulation in the elderly (pp. 33-54). Springer.

Sternberg, R. J., Jarvin, L., & Grigorenko, E. L. (Eds.) (2009). Teaching for wisdom, intelligence, creativity, and success. Corwin.

Tillich, P. (1963). The courage to be. Yale University Press.

Weststrate, N. M., & Glück, J. (2017). Hard-earned wisdom: Exploratory processing of difficult life experience is positively associated with wisdom. Developmental Psychology, 53(4), 800–814. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000286

Wong, P. T. P. (2005a). A course on the meaning of life (Part 3): What is your life intelligence (LQ)? International Network on Personal Meaning. https://www.meaning.ca/archives/MOL_course/MOL_course3.htm

Wong, P. T. P. (2005b). A course on the meaning of life (Part 1). International Network on Personal Meaning. https://www.meaning.ca/archives/MOL_course/MOL_course1.htm

Wong, P. T. P. (2005c). A course on the meaning of life (Part 2): How should we then live? International Network on Personal Meaning. https://www.meaning.ca/archives/MOL_course/MOL_course2.htm

Wong, P. T. P. (2005d). A course on the meaning of life (Part 4): What is the meaning of life? Does it matter how you answer this question? International Network on Personal Meaning. https://www.meaning.ca/archives/MOL_course/pdfs/mol_course_4.pdf

Wong, P. T. P. (2010). Meaning therapy: An integrative and positive existential psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40(2), 85-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-009-9132-6

Wong, P. T. P. (2012). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3-22). Routledge.

Wong, P. T. P. (2017, October 3). Lessons of life intelligence through life education [Invited talk]. Tzu Chi University, Hualien, Taiwan. http://www.drpaulwong.com/lessons-of-life-intelligence-through-life-education

Wong, P. T. P. (2020). Made for resilience and happiness: Effective coping with COVID-19 according to Viktor E. Frankl and Paul T. P. Wong. INPM Press.

Wong, P. T. P. (2022a, February 4). Existential positive psychology for living a positive life [Keynote]. Positive Psychology for Positive Life Virtual Conference. http://www.drpaulwong.com/existential-positive-psychology-for-living-a-positive-life/

Wong, P. T. P. (2022b, April 19). What really matters in the darkest hour: The 3 essentials of life intelligence (LQ) for career success [Keynote]. University of New Brunswick. http://www.drpaulwong.com/what-really-matters-in-the-darkest-hour/

Wong, P. T. P. (2022c, April 26). The best possible life in a troubled world: An existential positive psychology perspective [Symposium]. Positive Psychology in Cultural and Contextual Perspectives. http://www.drpaulwong.com/the-best-possible-life-in-a-troubled-world-an-existential-positive-psychology-perspective

Wong, P. T. P., & Bowers, V. (2018). Mature happiness and global wellbeing in difficult times. In N. R. Silton (Ed.), Scientific concepts behind happiness, kindness, and empathy in contemporary society. IGI Global.

Wong, P. T. P., Arslan, G., Bowers, V. L., Peacock, E. J., Kjell, O. N. E., Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T. (2021). Self-transcendence as a buffer against COVID-19 suffering: The development and validation of the self-transcendence measure-B. Frontiers, 12, 4229. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648549

Wong, P. T. P., Cowden, R. G., Mayer, C.-H., & Bowers, V. L. (in press). Shifting the paradigm of positive psychology: Toward an existential positive psychology of wellbeing.

Yu, W., & Jing, W. (2013). Discussion on physical education in the context of life education. Shoudu Tiyu Xueyuan Xuebao/Journal of Capital Institute of Physical Education, 25(4), 333-337.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.